You’ve seen the ads promising more power, better throttle response, and that aggressive engine sound. But before you drop $300-$500 on a cold air intake, you need the unfiltered facts. This guide cuts through the marketing hype and breaks down exactly when these mods deliver—and when they’re just expensive engine bay jewelry.

What Is a Cold Air Intake and How Does It Work?

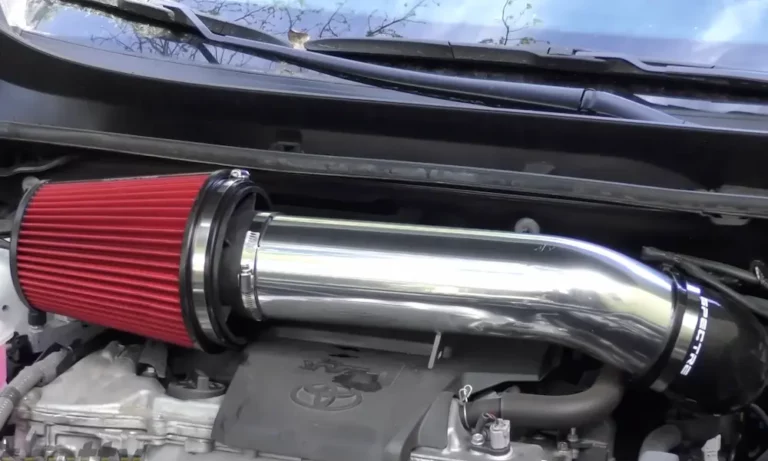

A cold air intake replaces your stock airbox with a streamlined tube and high-flow filter. The goal? Get denser, cooler air into your engine.

Here’s the science: Your engine is essentially an air pump. The more oxygen-rich air it inhales, the more fuel it can burn, and the more power it makes. Cold air is denser than hot air—it packs more oxygen molecules into the same space.

The engineering rule of thumb states that every 10°F drop in intake air temperature nets about 1% more horsepower. Sounds promising, right?

But there’s a catch. Stock intakes aren’t designed for maximum airflow. They’re engineered for quiet operation, long-term reliability, and fitting into cramped engine bays. Manufacturers add baffles, resonators, and corrugated tubing—all creating turbulence that restricts flow.

Aftermarket intakes strip away these restrictions. They use mandrel-bent aluminum tubes with smooth interiors to maintain laminar flow. The conical filters offer more surface area than flat stock filters. The result? Less resistance between the atmosphere and your throttle body.

The Turbo vs. Naturally Aspirated Divide

Not all engines benefit equally from cold air intakes. This is where the “worth it” equation splits dramatically.

Turbocharged Engines: The Sweet Spot

If you’re driving a turbo car, you’re in luck. These engines see the most consistent gains.

Here’s why: Any restriction before the turbo forces the compressor to work harder. It has to pull through that resistance to hit target boost pressure. This inefficiency creates heat and slows spool time.

A high-flow intake reduces this pre-compressor restriction. The turbo spools faster, runs cooler, and achieves boost with less effort. The gains multiply across the powerband.

Real-world data backs this up:

- Honda Civic 1.5T: Gains of 9-16 horsepower and 9-11 lb-ft torque with just an intake

- BMW N55 (3.0L Turbo): 10-17 wheel horsepower increase on stock tune

- Subaru WRX: 15-20 HP when properly tuned

The dollar-per-horsepower ratio on turbo cars ranges from $20-$50 per HP—not bad for a bolt-on mod.

Naturally Aspirated Engines: Diminishing Returns

NA engines tell a different story. They’re limited to atmospheric pressure (14.7 psi at sea level) to suck in air.

Modern NA engines come with surprisingly efficient stock intakes. OEM engineers already optimized the intake length, diameter, and routing for the stock power level.

The 2024 Mustang GT proves this point. Independent dyno testing showed “little to no difference” between stock filters and high-flow drop-ins. Ford’s engineers left no low-hanging fruit.

For most stock NA cars, you’re looking at 2-5 HP gains—often within dyno measurement error. At $300-$500 for the intake, that’s $60-$250 per horsepower. Not exactly a performance bargain.

The exception? Older vehicles with genuinely restrictive factory airboxes. Late ’90s trucks and economy cars often shipped with inadequate induction systems that choked airflow.

The Heat Soak Problem Nobody Talks About

Here’s where marketing materials conveniently go silent: location matters more than flow.

Many “cold air intakes” are actually hot air intakes in disguise. They’re called “short ram intakes”—open filters sitting directly in the engine bay.

Under your hood, temperatures regularly hit 150°F or higher. Exhaust manifolds radiate heat exceeding 1,000°F. Your radiator dumps waste heat directly into the engine compartment.

That open cone filter? It’s sucking in superheated air.

Remember that thermodynamics principle? Hotter air is less dense. Lower density means fewer oxygen molecules. Fewer oxygen molecules means less power—even if the filter flows beautifully.

Testing on the Honda S2000 confirmed this paradox. Open intakes flowed better but ingested hotter air during idle and low-speed driving. The result? Higher intake air temperatures than stock, negating the flow advantage.

The material matters too. Polished aluminum intake tubes look fantastic, but aluminum has high thermal conductivity. It absorbs radiant heat from the engine and transfers it directly to your air charge. You’ve basically installed a heater pipe.

Stock airboxes use plastic specifically because it insulates. They route fresh air from the fender or front bumper—away from engine heat. This thermal management often trumps the flow benefits of aftermarket systems.

The fix: Look for intakes with heat shields or fully enclosed airboxes. The best systems relocate the filter to the fender well or bumper opening. Yes, they’re more expensive and harder to install. They’re also the only ones that deliver on the “cold air” promise.

Filter Technology: The Flow vs. Protection Trade-Off

Let’s address the elephant in the intake tube: filtration efficiency.

Most performance intakes use oiled cotton gauze filters. Companies like K&N built their reputation on them. The design uses coarse cotton fibers coated in tacky oil. The open weave flows air easily while the oil traps dirt.

Physics demands a compromise between flow and filtration. To flow more air through the same surface area, the media must be more porous.

Independent testing consistently shows oiled filters allow more particulate matter past compared to OEM paper. One analysis found K&N filters had “half the filtering efficiency” of paper filters.

Used oil analysis reports from vehicles running oiled filters often show elevated silicon levels—evidence of dirt ingestion. In dusty environments, this can lead to “dusting” of turbo compressor wheels and accelerated cylinder wear.

There’s another issue: MAF sensor fouling. If you over-oil the filter during maintenance, microscopic oil droplets can coat the Mass Air Flow sensor’s heated wire element. This insulation makes the sensor report incorrect airflow, causing the ECU to inject less fuel. You get hesitation, rough idle, and check engine lights.

K&N disputes this in their technical videos, claiming proper oiling prevents contamination. But the prevalence of user complaints suggests the margin for error is slim.

Better option: Dry synthetic filters from AEM or AFE. They eliminate MAF fouling risk and offer better filtration than cotton gauze, with only slightly less flow potential.

For daily drivers prioritizing longevity over peak power, stick with OEM paper or upgrade to a quality dry filter.

The Tuning Requirement Nobody Mentions

Here’s the critical detail that determines if your intake investment pays off: software calibration.

Modern engines use the MAF sensor to measure incoming air mass. The ECU translates the sensor’s voltage into an air mass value using a lookup table calibrated for the stock intake tube diameter.

If your aftermarket intake uses a larger diameter tube (common for maximum flow), air velocity decreases for the same mass flow. The MAF sensor detects this slower air and sends a lower voltage signal.

The ECU thinks less air is entering than reality. It injects less fuel. You’re now running lean (too much air, not enough fuel).

On adaptive systems like Honda and Ford, the ECU can self-correct during cruising using oxygen sensor feedback. But the corrections have limits. If the deviation exceeds about 15%, you get a “System Too Lean” check engine light.

It gets worse on some platforms. The Subaru WRX is notoriously sensitive to MAF scaling changes. Running any intake without a tune risks dangerous lean spikes during wide-open throttle. This causes detonation (knock) that can destroy pistons.

The community consensus on WRX forums is unanimous: intake without tune = engine time bomb.

Even on more tolerant platforms, you’re leaving power on the table. The ECU may close the throttle plate to maintain torque targets, completely negating your airflow improvement.

The real cost: That $350 intake needs a $600 tuning device (COBB Accessport, Hondata FlashPro) to unlock its potential. Suddenly your budget-friendly bolt-on is a $950 investment.

But here’s where it gets interesting: the combination of intake plus tune delivers 2-3x the gains of either alone. On a 2021 Mustang GT, testing showed the intake by itself added minimal power. Add the tune, and the combo produced 20-25 HP.

The intake becomes an enabling modification. It removes the bottleneck that limits what the tune can achieve.

The Sound Factor: Measuring Performance in Decibels

Let’s be honest: For many enthusiasts, the “worth it” equation has nothing to do with horsepower.

Stock airboxes are designed with NVH (Noise, Vibration, Harshness) attenuation as a priority. They use baffled chambers and resonators to silence intake noise. The average buyer wants a quiet cabin.

Remove those sound dampeners and you unleash the mechanical symphony.

On naturally aspirated V8s, you get a deep, guttural intake roar under acceleration. The engine’s breathing becomes audible—raw and visceral.

On turbocharged cars, the transformation is even more dramatic. The high-pitched whistle of the turbo spooling becomes clearly audible in the cabin. When you lift off the throttle, the bypass valve venting pressure creates that signature “psshhh” sound associated with tuner culture.

This auditory feedback changes the driving experience. Research in psychoacoustics shows drivers perceive louder vehicles as faster. Even with zero measurable power gain, the enhanced engine note makes the car feel more responsive and aggressive.

For someone building a car for street enjoyment rather than track times, this sensory enhancement alone often justifies the purchase price. You’re buying smiles per gallon, not peak horsepower.

Warranty and Legal Considerations

Before you install that intake, understand the potential consequences.

The Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act

Many people fear that aftermarket parts automatically void warranties. Not true—at least not legally.

The Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act protects consumers. Manufacturers must prove the aftermarket part caused or contributed to the failure before denying a warranty claim.

Scenario A: You install a cold air intake and your power window motor fails. The dealer cannot legally deny that claim—there’s no causal link.

Scenario B: You install an intake without a tune, run lean, and melt a piston. The dealer will absolutely deny your engine replacement claim, arguing the modification altered air/fuel mixture and caused damage.

The practical reality? While the law protects you, fighting a denial costs time and money. Some dealerships flag modified vehicles in their systems, complicating all future service.

CARB Compliance: The California Factor

If you live in California or states adopting CARB standards (New York, Colorado, Massachusetts, etc.), legality becomes critical.

Any part modifying the intake tract is considered “tampering” with emissions equipment unless it has a CARB Executive Order (EO) number.

To get an EO, manufacturers submit intakes for rigorous emissions testing. If they pass, they receive certification and a decal with an EO number.

CARB-legal intakes: Can be legally installed and will pass smog inspections. They cost more due to certification expenses.

Non-compliant intakes: Sold “for off-road use only.” Installing them on a street car in CARB states is illegal. You’ll fail smog inspection, forcing you to reinstall stock components every two years.

This “hassle cost” significantly diminishes the value proposition.

The Hydrolock Risk

Cold air intakes that mount filters low (in fender wells or behind bumpers) introduce a catastrophic failure mode: hydrolock.

Water is incompressible. If your low-mounted filter gets submerged during heavy rain or flooding, it acts like a vacuum—sucking water into the engine.

When water enters the cylinder during compression stroke, the piston can’t compress it. The crankshaft’s momentum forces the piston upward anyway. The connecting rod bends or snaps, often punching through the engine block.

This is a terminal failure requiring complete engine replacement—easily $8,000-$15,000.

Some manufacturers include bypass valves that open if the primary filter submerges, allowing air from the engine bay instead. Hydro-shields (water-repellent pre-filters) offer additional protection.

But the safest approach? If you live in flood-prone areas, choose a short ram intake that keeps the filter high in the engine bay, despite the heat soak compromise.

Are Cold Air Intakes Worth It? The Final Verdict

The answer depends entirely on your vehicle and goals.

You Should Buy a Cold Air Intake If:

You drive a turbocharged vehicle. The mechanical advantage of reducing pre-turbo restriction delivers tangible gains in throttle response, spool time, and overall efficiency. Dollar-per-horsepower ratio is reasonable at $20-$50 per HP.

You’re planning to tune. As a supporting modification for an ECU remap, the intake removes a bottleneck that limits what the software can achieve. The combination delivers 2-3x the gains of either mod alone.

You value the sound. If induction roar and turbo noises enhance your driving enjoyment, the cost is justified by improved driving experience—even without measurable power gains.

You’re building a show car. The visual upgrade in the engine bay and the ability to tell people “it’s got a cold air intake” has social value in the enthusiast community.

Skip the Cold Air Intake If:

You drive a stock naturally aspirated commuter. Expecting noticeable power gains on a modern NA engine without a tune is unrealistic. At 2-5 HP for $300-$500, you’re paying $60-$250 per horsepower—terrible ROI.

You live in dusty or flood-prone areas. The risks of accelerated engine wear (from reduced filtration) and hydrolock (from water ingestion) outweigh marginal performance benefits for a daily driver.

You can’t afford the tune. On sensitive platforms like the Subaru WRX, running an intake without proper calibration risks catastrophic engine damage. The intake alone is worse than useless—it’s actively dangerous.

Your warranty matters. While Magnuson-Moss protects you legally, the practical hassle of fighting denied claims isn’t worth the minimal gains on most vehicles.

The Smart Approach

If you’ve read this far and still want a cold air intake, here’s how to maximize value and minimize risk:

Choose a sealed or well-shielded system that prevents heat soak. The “cold” in cold air intake matters more than the “air” part.

Select a dry synthetic filter to protect your MAF sensor and improve filtration efficiency compared to oiled cotton gauze.

Budget for a tune from day one. Don’t buy the intake thinking you’ll “add a tune later.” The combo is what actually delivers results.

Research your specific platform. Join forums for your exact make and model. Real owners share dyno results, common issues, and which brands actually deliver.

Consider a drop-in high-flow filter first. For $50-$80, you get most of the sound enhancement and minor flow improvement without the warranty risk, installation complexity, or heat soak problems of a full intake replacement.

The cold air intake occupies a weird space in the modification hierarchy. It’s simultaneously over-hyped and genuinely useful—depending entirely on context. For the right vehicle with the right supporting mods, it’s a crucial piece of the performance puzzle. For everything else, it’s an expensive way to make your engine breathe slightly better while looking good at Cars & Coffee.